Protecting People in Paradise—The Kauai Resilience Center

Mike and Tessa South stayed near the beautiful Hanalei Bay while visiting Hawaii in September 2023 to attend a planning meeting with community leaders regarding the Kauai Resilience Center.

Beauty blesses the North Shore of Kauai. The Kalalau Trail starts at the white sands of Ke'e Beach, with water calm for snorkeling or swimming, and a breathtaking view of the 17-mile-long NaPali Coast. The crescent-shaped beach at Hanalei Bay features a pier built in 1892 and spectacular sunsets. Ancient volcanos left lava tubes and tunnels at nearby Tunnels Beach, and the Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge features monk seals and seabirds of all kinds. Sea turtles and dolphins frolic, along with experienced surfers, attracted to Kauai’s North Shore by some of the most powerful waves in the world. Not far away stretches Waimea Canyon, 3,000 feet deep and 10 miles long. On a recent trip, Mike South, President of Monolithic, and his family tasted the most delicious chocolate sourced entirely in Kauai.

In 1992, Hurricane Iniki demonstrated how tender and vulnerable this paradise could be. The 130 to 160-mile-per-hour winds damaged 41 percent of Kauai’s 15,200 homes, injuring 100 and killing seven people. The Category 4 storm caused $3 billion in damage, and Iniki was one of 11 Central Pacific tropical cyclones during the El Niño season between 1990 and 1995.

“It could happen again,” said Jill Lowry, director of Anaina Hou Community Park.

How shall peace be protected in paradise? Lowry and Jeff Murray, a board member for the Western Fire Chiefs Association and the Hawaii Fire Chiefs Association have been pondering new possibilities. What if hurricanes could howl, fires could flame, and people could be protected on the island, secure in structures where no harm could enter?

When disasters bear down on the main continent, resources flow from all the adjoining states, Lowry said, and yet Hawaii, as an island state, needs extreme self-sufficiency. If disaster strikes, sometimes it’s possible to get into cars and drive away from the troubles—but on an island, there is no place to go but into the ocean, fierce and raging. Their research has led them to create a plan featuring three Monolithic Domes designed to withstand whatever winds may rise.

“The Monolithic Dome will survive and be almost intact when all is said and done,” Murray said. “In Category 5 hurricanes, even the most well-built homes fly away, but domes won’t. And inside a Monolithic Dome, people are safe from flying debris. The multifaceted protection of the Monolithic Dome beats other construction options. I believe Monolithic Domes can handle all aspects of nature out of the tsunami zone, as they can provide shelter and keep people out of harm’s way.”

“In some conditions, firefighting is nearly impossible,” he said. “When a fire is moving at 85 miles per hour downhill, burning vacant land and brush, everything downwind becomes preheated, and there’s no place to run.”

“People in domes could survive as long as they are not inhaling too much smoke,” said Murray. “With those things in place, people could be completely safe. A fire moving at 85 mph doesn’t stay a long period of time, but things around might burn for 30 minutes or so. If there were multiple domes, very little off-gassing would be happening. If I had it my way, I would propose that every church, gymnasium, community center, and school have at least one Monolithic Dome for protection.”

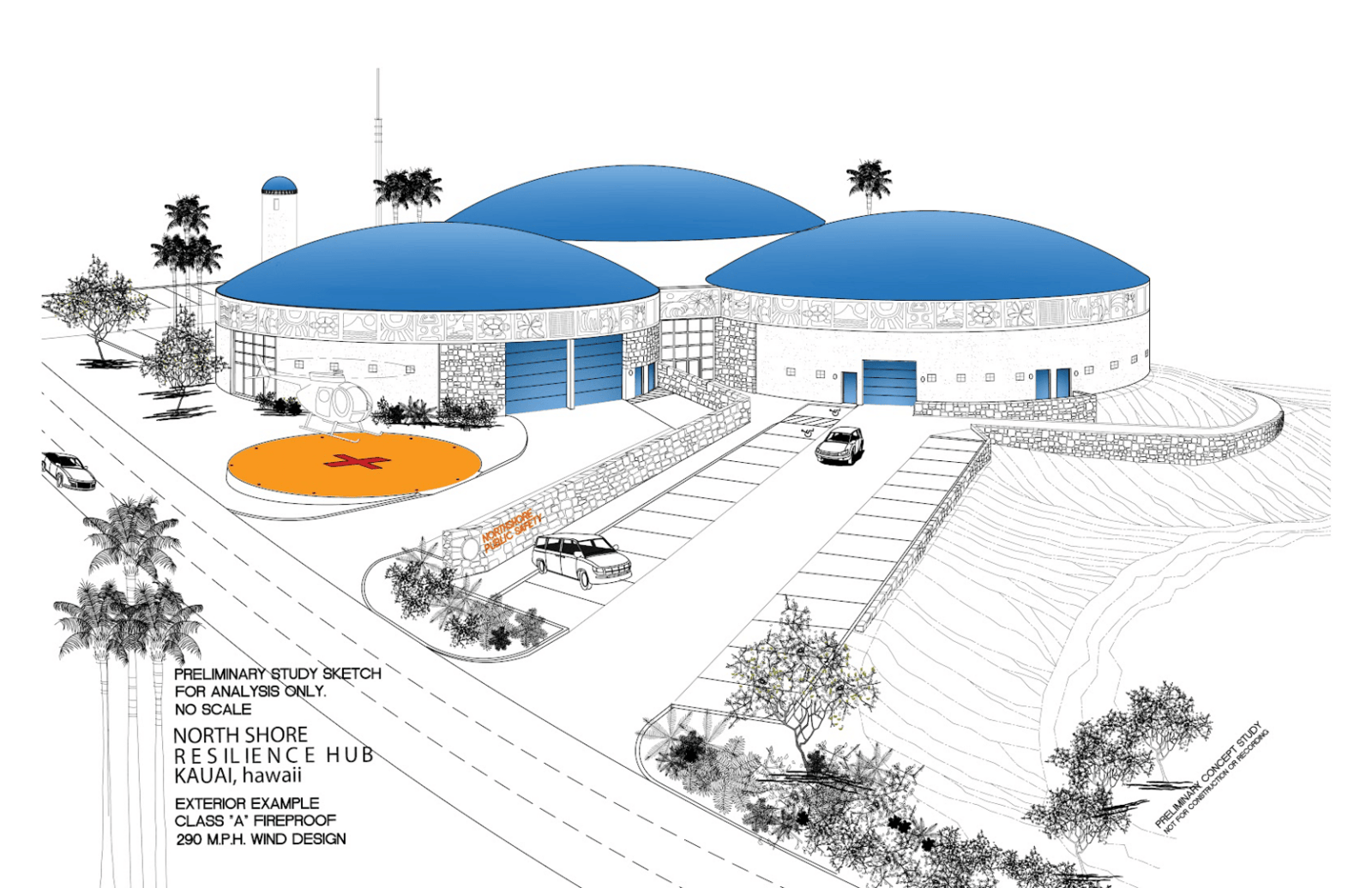

They found Rick Crandall, an architect who has completed designs or consulted on hundreds of successful Monolithic Dome projects, and they have envisioned a plan that calls for three Monolithic Domes that would house a fire department, police, emergency medical personnel, and public shelters for up to 450 people. The domes would be an emergency control center, with separate stand-by power for communications and control.

“The center bays can house six emergency vehicles, including a helicopter with folding rotors,” Crandall said. “The ambulance and small first aid center can be greatly expanded to become a MASH unit in case of emergencies.”

Lowry said the Kauai Resilience Center would include a huge commercial kitchen and an interior depth built to provide short-term shelter for 1000 to 1500 people.

“Rules changed after Iniki,” said Lowry. “Homes built to code must be able to withstand Category 3 hurricanes, but that’s only for new homes—and the upgrades are expensive.”

“I was a fire person for almost 36 years, and we respond to everything,” Jeff Murray said. “Why not build structures that protect people so there are fewer people to respond to? You can’t bring back life. Protecting life is part of my passion. The more people can protect themselves and survive incidents, the better. The rest of it can be worked out.”

Lowry has been working on fundraising to create the Kauai Resilience Center. She said that few structures on Kauai could survive winds stronger than a large tropical storm. She warns another hurricane like Iniki could strike at any time, or a fire could rage, and she wants Kauai to be ready.

“It will have to be a community effort, and it’s got to become a wave as people recognize that the ones they love are in danger here unless we build shelter from forest fires and hurricanes,” Lowry said. “We live in the middle of the ocean on a limited land mass.”

In the spring, she plans to go to Washington, DC, for the Hawaii on the Hill event in hopes of generating interest and raising the funds essential for the project. Kauai has become known as a haven, and 52 new multimillionaires and billionaires have moved to the island since the pandemic began.

“High net worth individuals don’t always interact with the community at large,” Lowry said. “We’ve looked for USDA loans, revenue funds, FEMA, and we’ll ask senators for appropriations. Our fundraising push begins in December, and we need to find that first seven-figure donation to get this thing moving. That first gift will generate confidence, and more will follow.”

Jill Lowry presents the preliminary sketch of the Kauai Resilience Center and welcomes community leaders to the planning meeting.

Tessa (at left) and Mike South pose for a photo with Jill Lowry (center right) and President of Kauai’s Chamber of Commerce Mark Perriello (at right) after meeting with community leaders in Kauai in September 2023.

In September 2023, Mike South of Monolithic met with the mayor, the director of housing, the head of building permits and construction, the fire chief, and other community leaders to discuss practical aspects of the project.

Jeff Murray also attended the meeting. “On a strictly practical level, domes also require less maintenance than other buildings and last four to five times longer than any other structure,” he said. “Most of all, even more important than saving money, they want to save lives. Creating Monolithic Dome shelters will do that, they agreed, while providing space for much-needed services.

"First, you must survive,” Murray said. “You’re alive now. You’re finished with the crisis situation. You can go on to the next project. If you’re not alive, then it really doesn’t matter.”

Murray spent years in the Air Force as a fireman before becoming a fire chief in Maui, retiring in 2019. He was born and raised in Hawaii and has seen extreme changes.

“People are taken aback by how a Monolithic Dome looks,” he said. “They are so used to seeing everything lineal, and not everybody has the ability to see creatively. You have to think outside the box, quite literally. Any time you change the environment on earth, the dynamics and everything else changes. You have to adapt the rules for the new game. We must keep changing.”

Lowry concurred with Murray. All along the North Shore of Kauai, there rises a subtle yearning for safety. It begins as a whisper on the wind, the gentleness of a zephyr, bringing the scent of soothing frangipani, but Lowry feels a sense of urgency. She would like this project to inspire others so that every part of Kauai could have the security of Monolithic Dome protection.

“If you’re dead, it’s game over,” she said. “If you’re alive, it may be a tough road back, but you’ve got a chance. We need this now, before the next disaster.”

For more information or to donate, visit kauairesilience.org.

Mike and Tessa South’s son, Frankie, looks out over the Anaina Hou Community Park.