Maui Rises from Ashes After Losses in Lahaina

A small show of support for the families in the town of Lahaina who lost everything when brushfires ran wild on Hawaii’s second largest Island, Maui.

The recovery efforts on Maui continue unceasingly as families, homes, and businesses rise from the ashes, exhaustion, and grief caused by the wildfires of August 2023.

“Everyone’s overwhelmed,” said Tapani Vuori, general manager of the Maui Ocean Center in Makawao. “It took more than a month to get things coordinated and cohesive. We had forty volunteers, but at first, the NGOs (non-governmental organizations) simply were not ready.”

In early August, the Hawaii Wing of the US Civil Air Patrol conducted two aerial surveys, capturing photos and videos of the extensive damage caused by the Maui brush fires ignited by downed power lines.

On August 8, before a wildfire turned into an urban fire and swept through Lahaina, whipped wild by 85-mile-per-hour wind, the Maui Ocean Center had 1,467 visitors. On August 22, they had 106 visitors—a 95 percent drop. On August 23, all the hotel general managers and business owners on Maui were invited to the Monolithic Dome at the Center, called the Sphere, to discuss how the community could come together cohesively.

“We still have beautiful areas everywhere, and we want tourists here, so those dollars in circulation can help us recover,” Vuori said. “We want respectful, caring, compassionate tourism, but of course, no tourist needs to go to Lahaina.”

As he speaks, his strong voice cracks with emotion. Economic loss, while intense, appears to be the least of Maui’s losses. The fire burned 2,170 acres, damaging or destroying 2,207 structures and taking at least 115 lives. Vuori speaks with respect for the rights of indigenous people to have a strong voice in how to respond to the disaster, and he is mindful of his own immediate responsibility for stewardship of the Ocean Center, as well as its place in the larger tragedy.

“I made a commitment to pay all of our people here full pay for two months,” he said. “We don’t need to be sending people home, no matter what the numbers. And all the money we can donate to help will come from tourism.”

One employee lost four family members and a home. Two others lost their homes as well. The litany of loss grows long near Lahaina, 15 miles away.

“For three and a half weeks, we had many people camping here in the parking lot,” Vuori said. “We were dealing with so many displaced families. We fed them, sheltered them, and organized assistance. We sent our employees to help set up NGO functions and offices.”

The Maui Ocean Center brought practical resources to the parking lot, including crisis counselors, wellness practitioners, energy healers, acupuncturists, and massage therapists. They dealt with the immediate grief and crisis with all the kindness and comfort they could muster.

Families under duress struggled to complete bureaucratic paperwork to meet their most basic needs. One family living in a tent in the parking lot of the Ocean Center had lost all they owned in the world, and after completing extensive paperwork, they received a $5000 voucher from FEMA for a stay in an Airbnb. They had no livelihood, no schools for their children, no jobs, no homes—but they could stay in an Airbnb until the dollars ran out. They had outrun the fire. They had their lives, and they had each other.

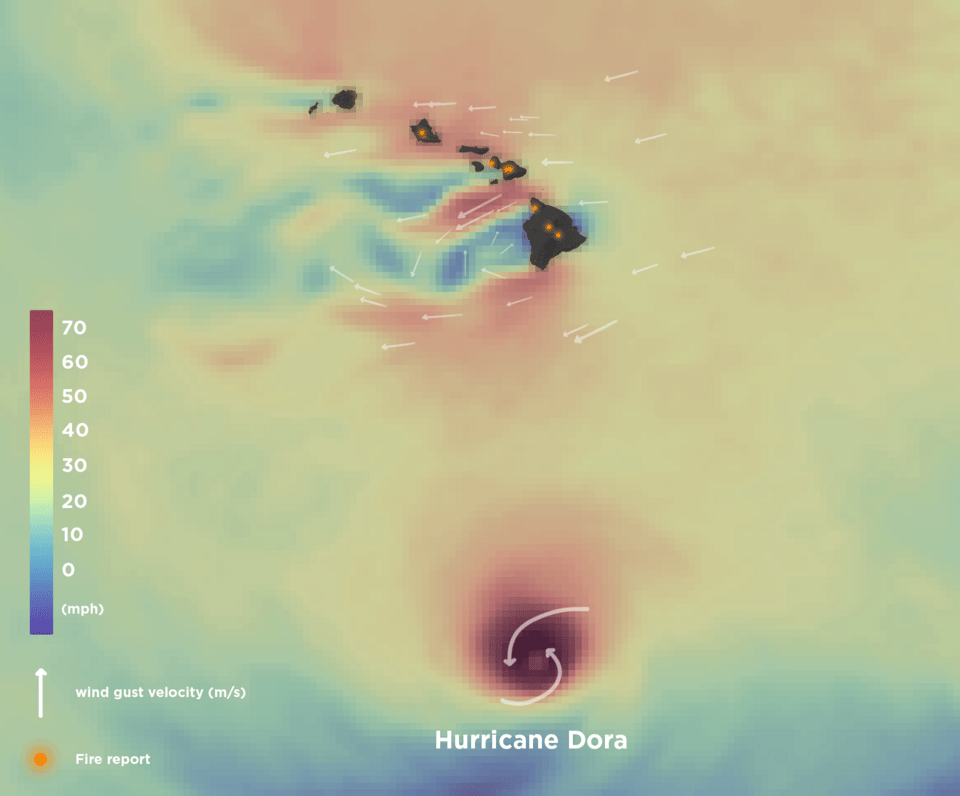

This graphic illustrates the high wind intensity in and around Hawaii on the morning of August 8, 2023. The roaring winds stoked and spread the fires on Maui which decimated the historic town of Lahaina.

“The temperature of that fire rose to 2000 degrees,” Vuori said. “It was a horizontal fire with those winds. People taking shelter died in their cars, in their homes, and now their ashes mix with the ashes of all else lost.”

The fire began as a wildfire but became an urban fire with a high level of toxicity. Ash analysis showed a very high level of arsenic, dioxin, and polyfluorocarbons, which destroy the ozone. Vuori has taken money from his own pockets to help supply personal protection for recovery efforts, including masks, respirators with Tyvek suits, and boots.

“With 9-11, we saw cancer clusters among rescue workers, five and ten years afterward,” he said. “We don’t want that to happen here.”

The Maui Ocean Center has been working actively with the community to support recovery efforts in every way possible, both large and small. On their website, they offer Maui Strong t-shirts for $35, and the Center uses $10 apiece to pay for the shirts, donating the remaining $25 from each shirt to Hawaii Community Foundation’s Maui Strong Fund.

“We need all hands on deck,” Vuori said. “It is an all-community effort.”

The town of Lahaina, with a population of 12,702 in the 2020 census, had more than two million tourists annually, representing 80 percent of Maui tourism. Since the fire, Maui has lost more than $12 million daily, according to Carl Bonham, executive director of UHERO, the Economic Research Organization at the University of Hawaii.

“We need to bring money back into this economy to allow Maui to recover faster,” Vuori said. “On the economic side, Norwegian Cruise Lines had suspended port of calls to the end of the year, but they re-examined that decision, and on Sept. 3, they started coming back. We must find a way to take charge of our future, including our economic future, or the disaster will be compounded for us.”

The crew from the Maui Ocean Center shows off their new Maui Strong T-shirts. For sale on their website, the Maui Ocean Center will donate $25 per T-shirt to the Hawaii Community Foundation’s Maui Strong Fund.

Despite the downturn in visitors, at the end of August, the Maui Ocean Center offered free admission to all Hawaiians, and 8,000 people visited the center. The Center also offers inexpensive admittance for local people on the weekends to help lift spirits.

“We want to return to some semblance of normalcy,” Vuori said.

Mike South, co-owner of Monolithic, went on a business trip to Hawaii in October and visited the Maui Ocean Center with family.

“The price of housing is such that many working-class people have nowhere near affordable housing,” Mike South noted. “With the fires in Lahaina, there is a spike in demand that will drive up the cost of rented housing and drive more people out of their homes. Many people are living in their cars. It’s hard to believe a place with so much beauty has so much suffering.”

Long-standing issues of water rights, cultural rights, and indigenous rights have been brought to light by this fiery disaster. The island’s infrastructure had not been engineered to carry all the heavy demands placed on it by wastewater or the roads prepared for heavy traffic.

“Grief brings a lot of anger, and it will take time to resolve,” Vuori said.

Recovery includes the protection of marine ecosystems. The Maui Ocean Center is a sanctuary, and ash floating into the ocean could cause significant damage to marine life. The county and the Environmental Protection Agency made a decision to use a compound called Soiltac, a copolymer dust control agent that can bind the ash together so the Army Corps of Engineers can scoop it up. They must scoop fast, though, as winter rains rise, and concerns have been voiced about plasticizers. Soilworks CEO Chad Falkenberg told the Maui County Council that Soiltac would not degrade into toxic microplastics.

“Now we will need to envision a new future,” Vuori said. “It’s a tragic disaster. Somehow, we have to make it a transformative opportunity so Maui can move forward.”

Multiple agencies collaborated in the aftermath of the Lahaina fires in August. Members of the Hawaii Army and Air National Guard and the U.S. Army Active Duty and Reserve worked to support Maui County authorities and first responders’ efforts. Local businesses and community organizations have banded together to help affected community members.

U.S. Army National Guard Spc. Sean Walker / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Many local groups are working together to help Maui recover from the terrible fire. In addition to his work at the Maui Ocean Center, Vuori is also vice president of the Maui Triangle Association, which advocates for preserving Lahaina’s sense of place and culture in its residential villages. The president, Paul Cheng, donated ten acres for a temporary school and housing.

The county of Maui set up a new website—Support Local—to support local businesses.

Maui Now reports that Mayor Richard T. Bessen, Jr. has appointed Josiah Nishita to lead the new Office of Recovery. The mayor has weekly meetings with the newly formed Lahaina Advisory Team. The team includes three residents who lost their homes in the fire: Kim Ball, founder and president of Hi-Tech Maui; Laurie DeGama, president of Lahainaluna PTA and owner of No Ka Oi Deli; and Rick Nava, president and owner of MSI Maui. DeGama and Nava graduated from Lahainaluna High School, as did two other team members, Kaliko Storer, Pu'u Fukui Watershed operations supervisor, and Archie Kale, leader of Maui Ocean Rescue and Safety, a ninth-generation resident of Lahaina who was inducted to the Duke Kahanamoku Foundation Hawaii Waterman Hall of Fame.

“It will take all of us working together,” Vuori said. “We have so many legacy situations, systemic issues, and this time calls for truly transformational changes.”