Raising and Razing Ream's Turtle

Originally named Winter Garden Ice Rink when it debuted at BYU’s 1963 Winter Carnival, the Ream’s Turtle was a triaxial elliptical dome, 240 feet long, 160 feet wide and 40 feet high at its center.

“It was a very good building for a very long time—but that’s progress, I guess,” said Dr. Arnold Wilson about the February 11, 2006 razing of a historic, thin shell concrete dome in Provo, Utah.

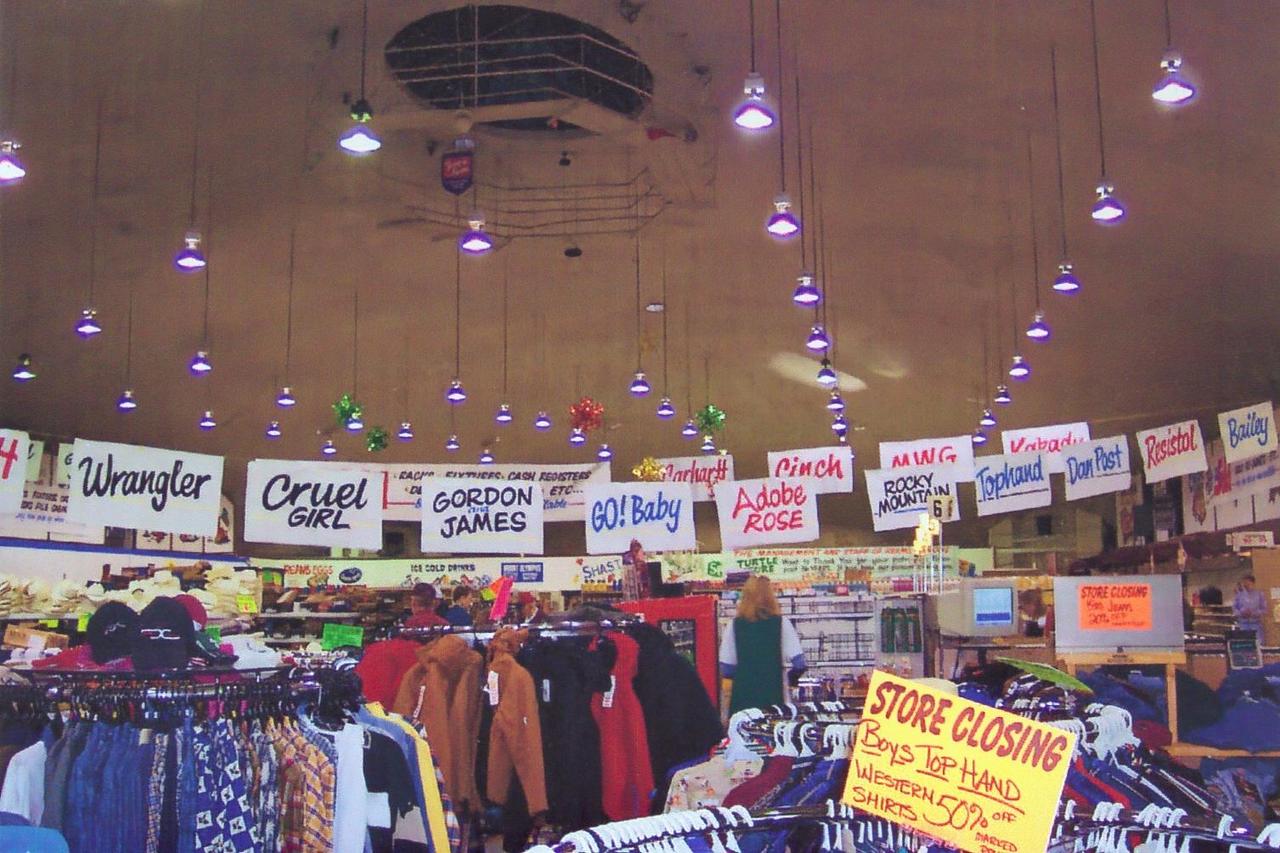

Because of its shape, locals had dubbed the structure the Ream’s Turtle in 1967, when owner Paul Ream turned it into a giant general store that sold everything from groceries to Tony Lama cowboy boots.

But its history predates that 1967 conversion. It goes back to 1961, when Dr. Wilson, now Senior Consulting Engineer for the Monolithic Dome Institute and Professor Emeritus of Civil Engineering at Brigham Young University (BYU), was just working on his master’s degree.

History of the Thin Shell Dome

Young Wilson befriended Harry Hodson, an engineering professor at BYU who gave him articles about and sparked his interest in thin shell domes. As a result, Wilson asked Hodson if he could do his master’s thesis on thin shells. Professor Hodson not only agreed but invited his eager protege to join him in the engineering of a giant ice skating rink—the dome that eventually became the Ream’s Turtle.

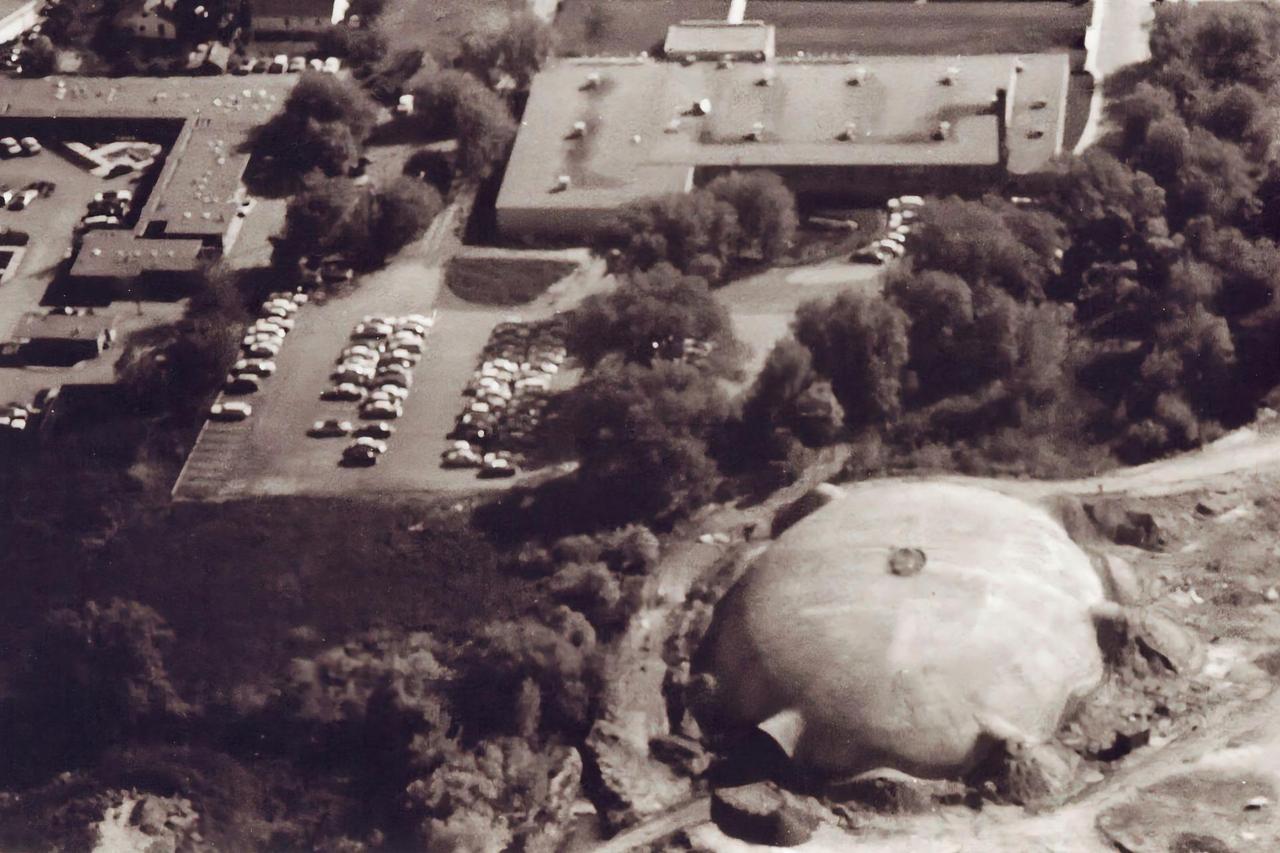

Originally named Winter Garden Ice Rink when it debuted at BYU’s 1963 Winter Carnival, the Ream’s Turtle was a triaxial elliptical dome, 240 feet long, 160 feet wide and 40 feet high at its center.

“We molded that mound into the earth-form we used to shape the dome,” Dr. Wilson said. “It was free and it really produced a very, very economical building. But it wasn’t easy. Today, of course, we use Airforms and that makes it much easier.”

Flamed Interest

Asked if it further flamed his interest in thin shells, Dr. Wilson said, “Oh, very much so! Boy, did it ever!” He recalled that Architect Lee Knell wanted a giant ice rink with an open interior, uninterrupted by posts or poles. So Knell, Hodson and Wilson got to work.

“We came up with a three-dimensional elliptical structure,” Dr. Wilson said. “But in those days, we didn’t have computers to analyze the engineering, so we decided to build and test a model in Lee Knell’s yard. And in the middle of that project, Professor Hodson accepted a new job and moved to Ohio.

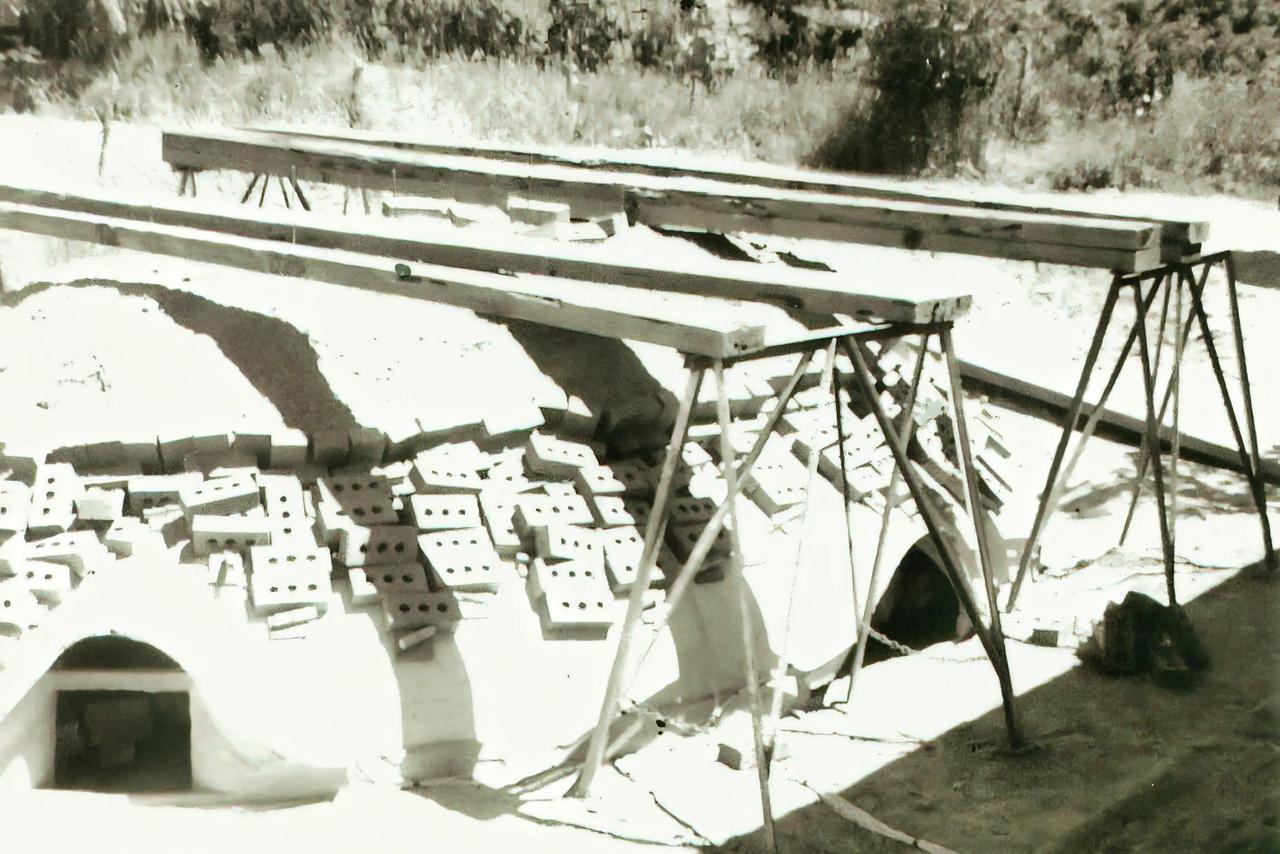

Without computers to help analyze the shape, Wilson said they created a 1/12 scale model by first creating this mound of earth.

They applied a concrete layer over the scale model’s earth mound. After it cured, they excavated the earth and then load-tested the finished model to failure. These tests proved the design and prepared the project for full-scale construction.

“So, using a mound of earth to form its shape, I built the model—a one-twelfth scale model made of reinforced concrete that looked like a giant dollhouse,” Dr. Wilson added. “I load tested it to failure and went back and made changes in the original design that matched the test results.”

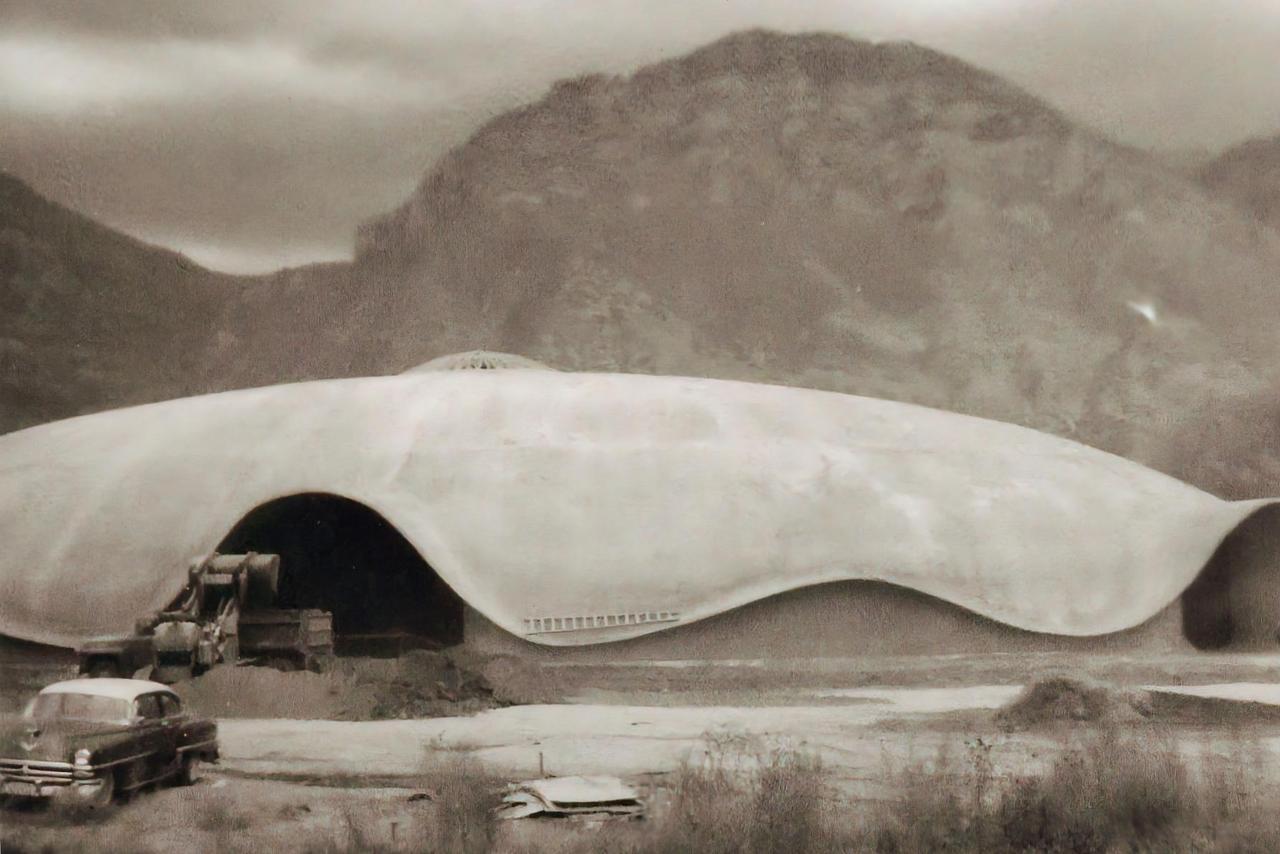

The beautiful swooping lines of the finished concrete shell. Note the front-end loader removing earth from inside the concrete shell.

Cost-Effective Construction

At a cost of about $75,000, Dr. Wilson said that he thinks the Ream’s Turtle was the most economical building of that size ever built. He described its cost-effective construction. “The site for the Ream’s Turtle was an old clay bed—actually a giant hole—created by Provo Brick and Tile, a company that excavated clay and made bricks for many years. When BYU began building its campus on a hill, they began filling that hole with material they excavated. After filling that hole, they hauled over an additional 40,000 cubic yards.

"We molded that mound into the earth-form we used to shape the dome,” Dr. Wilson said. “It was free and it really produced a very, very economical building. But it wasn’t easy. Today, of course, we use Airforms and that makes it much easier.”

The article, “Provo preps to say goodbye to oddly shaped landmark” in the Daily Herald of February 5 says, “…contractors heaped 40,000 cubic yards of dirt fill and sculpted it into a smoothly rounded dome with smaller mounds rippled around the perimeter. They braced it with a grid of steel bars that, if placed end-to-end, would stretch 21 miles. Then they sprayed on about four inches of concrete. Sprinklers moistened the roof for a month to prevent curling, and after the concrete shell dried, contractors spent three weeks scooping out and hauling away the dirt.”

Demolition of the Ream’s Turtle took two track-hoes, one equipped with a 5000-pound wrecking ball that continually circled the dome, bashing its concrete.

The demolition

So with all that history very much in mind, on a windy Saturday morning in February, Dr. Wilson watched the demolition of the Ream’s Turtle: “They scheduled a public affair, with the mayor and city council present for about noon. We got there at about 10 a.m. They were already working on the building as about 100 people watched.

"They used two track-hoes. One had a 5000-pound, steel, wrecking ball hanging from it. That ball had been going all around the dome, pounding its concrete, but avoiding the area around its five entrances. Nevertheless, it had knocked the concrete off in a strip four to five feet wide along most of the structure.

"As they continued preparing for the ceremony, someone hollered, ‘One last look. Come and take a look.’ About twenty onlookers ran over to one of the back entrances. At about the same instant, the second track-hoe, working on the dome’s other side, reached up and yanked down one of those entrances. That triggered it—zip—the beloved Ream’s Turtle collapsed in about 30 seconds.”

Hours of battering with the wrecking ball finally produced a strip four to five feet wide through which the grid of reinforcing steel bars could be seen. If placed end-to-end those bars would have measured 21 miles.

After smashing a line around the dome shell, with a nearly continuous cut, the shell is still standing—but don’t go inside.

According to the Daily Herald, that demolition cost more than the Turtle’s construction.

“It was a very interesting structure,” Dr. Wilson concluded. “I’m glad I was there at its beginning. I not only helped design it, but I helped build it. One day, as I just stood watching, the contractor said, ‘Well, if you’re going to be over here all the time, watching, you might as well tie steel.’ So I got a pair of pliers and began tying rebar.”

Since that memorable building of the Ream’s Turtle, Dr. Wilson became a Civil Engineering Professor at BYU—a forty-year career during which he inspired interest in thin shell domes among his students. Then in the 1970s, he met David B. South and began working with Monolithic. More recently, Dr. Wilson authored Practical Design of Concrete Shells, a text specifically written for engineers, architects, builders and students of civil engineering. With that book completed, Dr. Wilson retired.

The Turtle had five large entrances. After extensively pounding the concrete between its entrances, a track-hoe attacked one of those entrances and that finally triggered the structure’s collapse.

What David said about Reams

While working on this article, I asked David B. South, Monolithic’s president about the Ream’s Turtle’s collapse. Specifically, I wanted to know if David was surprised by what many described as the structure’s near-instantaneous fall.

“But it wasn’t,” David said. “I wouldn’t describe it as anywhere near instantaneous. That was a huge dome that took a huge amount of continuous battering. A very large section of it had to be systematically and significantly weakened before those track-hoes could bring it down. And then it only came down when one of those track-hoes began yanking on one of the entrances—a structure’s most vulnerable area.

"Notice the very large areas along the side of the dome that have had all of the concrete knocked out. Only the reinforcing bar is left. More than 50% of the support has been removed.

"Also consider that it was a 5000-pound wrecking ball that was swung against the dome. Think of the impact that has on a structure. Just the vibration created by such an impact is horrendous.

"And how many centuries do you think the Turtle would have survived if some ole meanies hadn’t beat the devil out of it with a wrecking ball?

"No, that demolition wasn’t quick at all. It took a lot to get it down,” he concluded.