Historical Footage of Building the First Monolithic Dome with Excerpt from ‘Think Round’

The following is an excerpt from David B. South’s autobiography Think Round: The Story of David B. South and The Monolithic Dome. It begins in the 1970s when David and his brothers owned and operated Souths Incorporated in Shelley, Idaho. Souths, Inc. had grown to be the largest foam application business in the Northwest….

In 1975, my brothers, Barry, Randy and I flew to California for our annual dinner meeting with the CPR Division of Upjohn. While there, CPR’s president asked me about our latest projects. I told him about my dome research and that I wanted to try to build a Monolithic Dome, and I described the entire process.

After I answered all his questions, he said, “So let’s quit talking and do it. Put up or shut up! What’s your first step?”

“It’s going to be expensive,” I replied. “I have to apply for a bank loan.”

“How much foam will you need?”

I told him I needed twelve thousand pounds—about $8,000 worth! He said, “All right. If you tell me that you’ll get this thing under construction, I’ll give you the foam.”

“Oh, I’ll get it under construction,” I said.

So he sent the foam—no strings attached. I’ve always been grateful to him for that. It pushed me over the top and reinforced my conviction of the do-ability of this project. Plus, it meant $8,000 that I didn’t have to borrow, so the loan value ratio on the building made it possible to get a lender.

The first Monolithic Dome was 105 feet in diameter. Built by David B. South and his brothers, Barry and Randy in 1975, they were awarded patents for their dome construction method in 1979 and 1980.

Funding, Engineering and an Airform

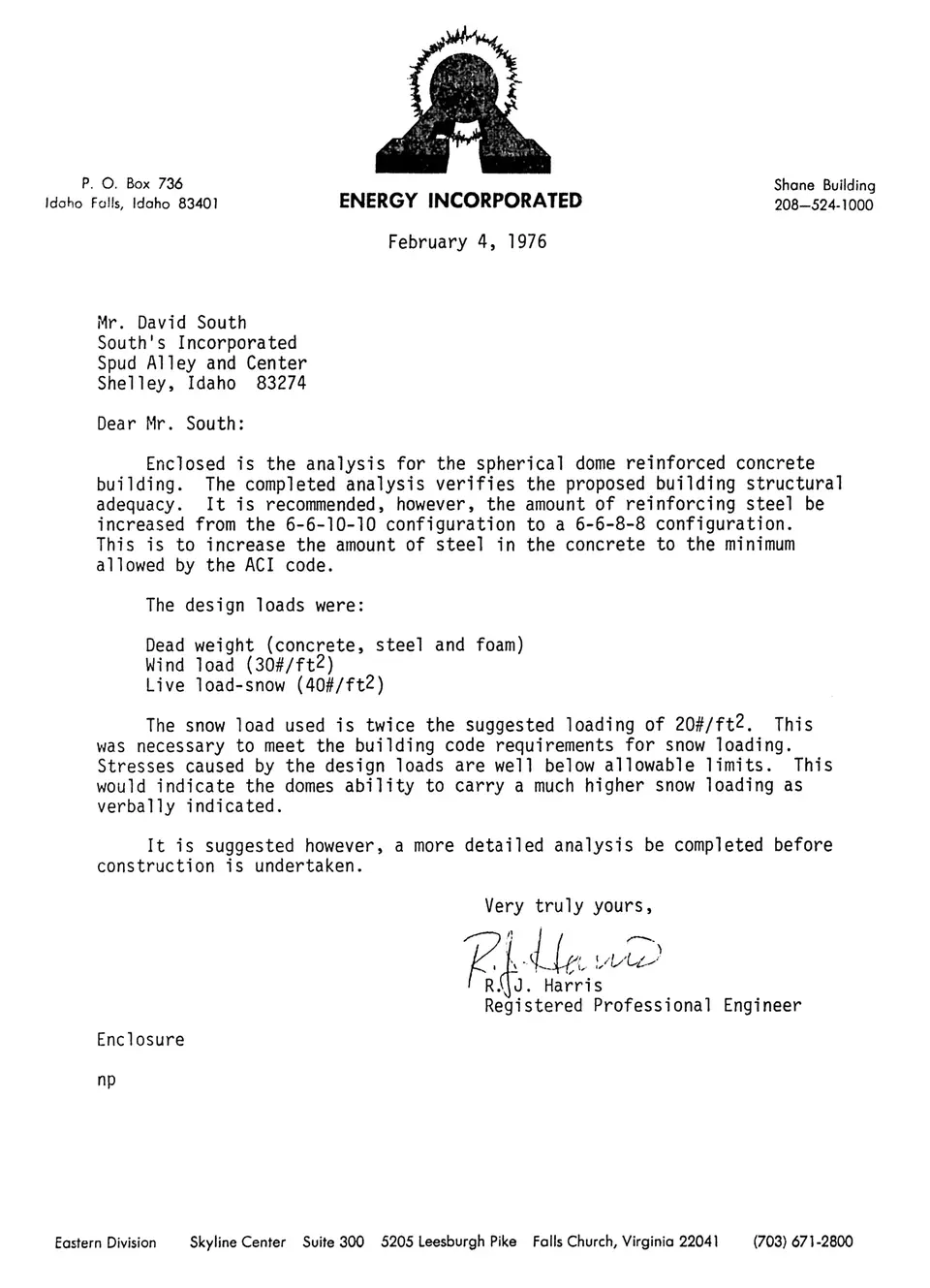

A letter from Energy Incorporated, the firm who provided the engineering for the first Monolithic Dome.

After our return from California, I applied for a loan with the Federal Land Bank; they insisted on seeing the engineering. So I hired a local engineer to do the thin shell engineering. At the time, I didn’t realize what a benefit he was. That engineer hand-calculated the whole thing—about eight pages of facts and figures that I gave to the Federal Land Bank, who agreed to the loan. I then applied to my local bank and borrowed against the commitment from Federal Land Bank.

I began searching for a company to make the Airform and finally found a company called Sinda in California. Sinda’s president agreed to build the Airform, provided I gave him the specifications. When I told him what the Airform was for, he told me I was crazy, but he’d build it anyway.

April 5, 1976

That trial Airform was made of material vastly lighter than what we use today. Instead of an airlock, it had a zipper, but it inflated properly. We tied it to the foundation with a drawstring, much like a drawstring on a bag.

Building that trial dome proved a comedy unto itself. Instead of the rebar we use today, our original engineering provided reinforcement with a mesh fabric, a welded wire fabric commonly called 6-6-10-10 Mesh. We measured our air pressure with a magnahelic, and I guesstimated just about everything we did, even the two inches of air pressure.

Barry South and another crew member attach the dome-shaped membrane to the central air plenum. One of Barry’s sons, Jason, wrapped in a blanket, looks on.

But we got it inflated and foamed. The foam presented no problem, and somehow we got the mesh placed. Then we started spraying the concrete.

I engaged a Salt Lake City firm that sprayed shotcrete in tunnels to do the concrete spraying. But the crew sent to us had very little experience. They used a Thompson Concrete Pump, that was new on the market, to spray in-place concrete—also a relatively new product. Simply not a lot was known about either the pump or the concrete!

We worked for three or four days with practically no good results. I called the boss in Salt Lake, bought the pump and sent the crew home. Then Barry, Randy and I began teaching ourselves the art of concrete spraying.

In the process, we learned to use rebar instead of mesh fabric. The mesh proved almost impossible to lay along a curved surface. In that first dome, we supplemented the mesh with rebar and that made me feel much better. We sprayed the concrete with a piston, mechanical pump that tended to plug. Usually, pressure created by the plug would then break something else. So for every hour we spent spraying, we spent two hours repairing. Eventually we got it done and I was very, very satisfied.

At the time, we thought that peeling the Airform off and reusing it was a good idea. So we did. We peeled the Airform off the dome’s outside and sprayed the outside of the dome with a half-inch of concrete.

The first Monolithic Dome was objectively homely, but the South brothers had achieved what they’d set out to accomplish. It took a lot of guts to build the prototype so large, but their risk paid off.

A Qualified Success

That was an ugly dome. There was no doubt about it. But to me, it was beautiful, sitting there, just off the side of the road in Shelley, Idaho. It meant that the Monolithic Dome was born.

I designed that first Monolithic Dome with a diameter of 105 feet and a height of 35 feet, furnished it with a CAT air system and rented it to a farmer for his five million pounds of Idaho potatoes.

First Monolithic Dome Gets Media Coverage

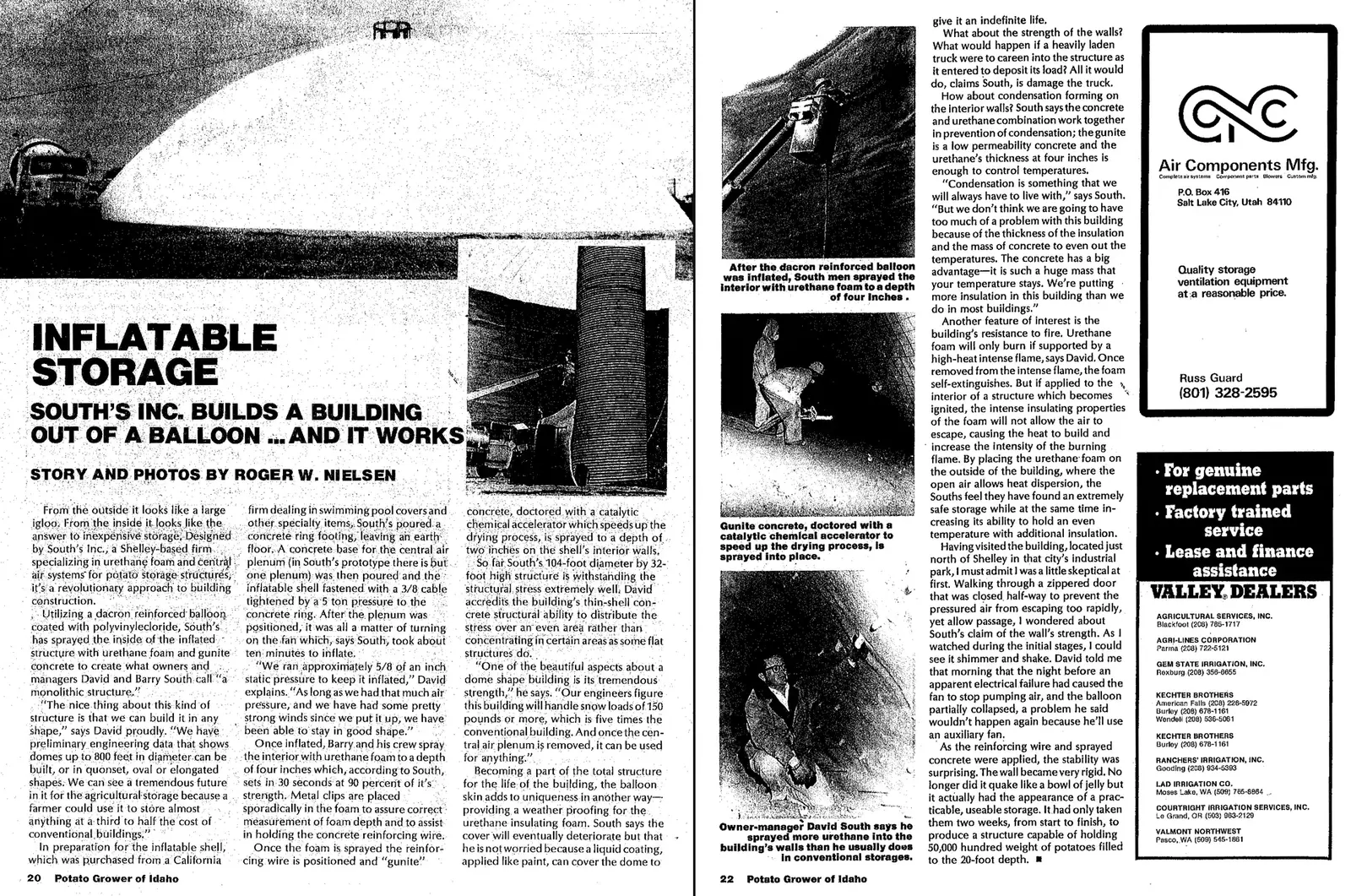

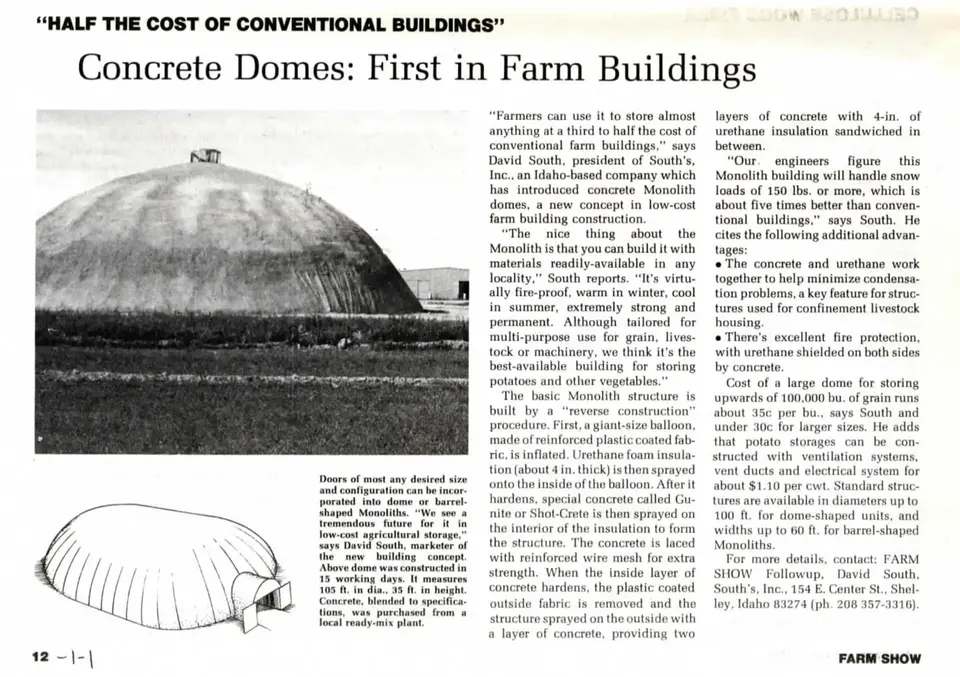

The 1977 charter issue of Farm Show Magazine featured a story about the first Monolithic Dome.

The Idaho Potato Grower magazine, with its nationwide readership of potato farmers, did an illustrated feature article on this first Monolithic Dome. Various other publications reprinted that article and some translated it into other languages, including Swahili. We began hearing from people all over the world. That was a mind-blowing experience; it strengthened my conviction that we had a building system for the future.

As Buckminster Fuller had proven, you can cover more space with a dome than with a structure of any other shape. Our engineering added to that premise: The Monolithic Dome would not only cover more space, but would be stronger than most other-shape structures.

Then too, by inflating an Airform and doing the construction inside of it, we would be largely weather-independent—an enormous benefit for construction personnel worldwide. With an in-place foundation and an inflated Airform, Monolithic Domes could be built in rain, snow or wind.

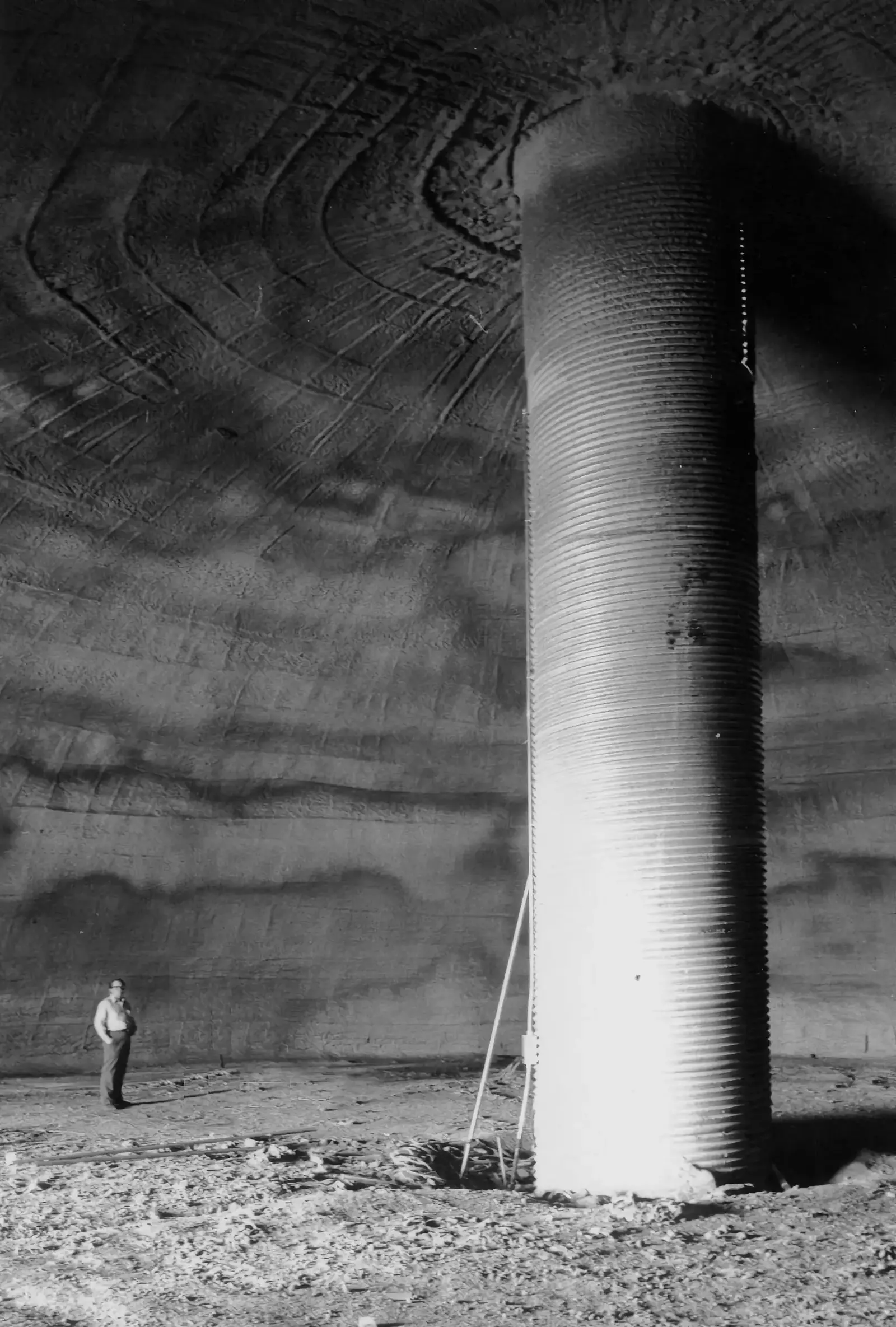

1976, David B. South stands inside the completed shell of the prototype Monolithic Dome. The concrete slab was poured soon after.

The South Brother’s brother-in-law, Gary Lund, gets a closer look at the attachment of the dome-shaped membrane to the circular footing.

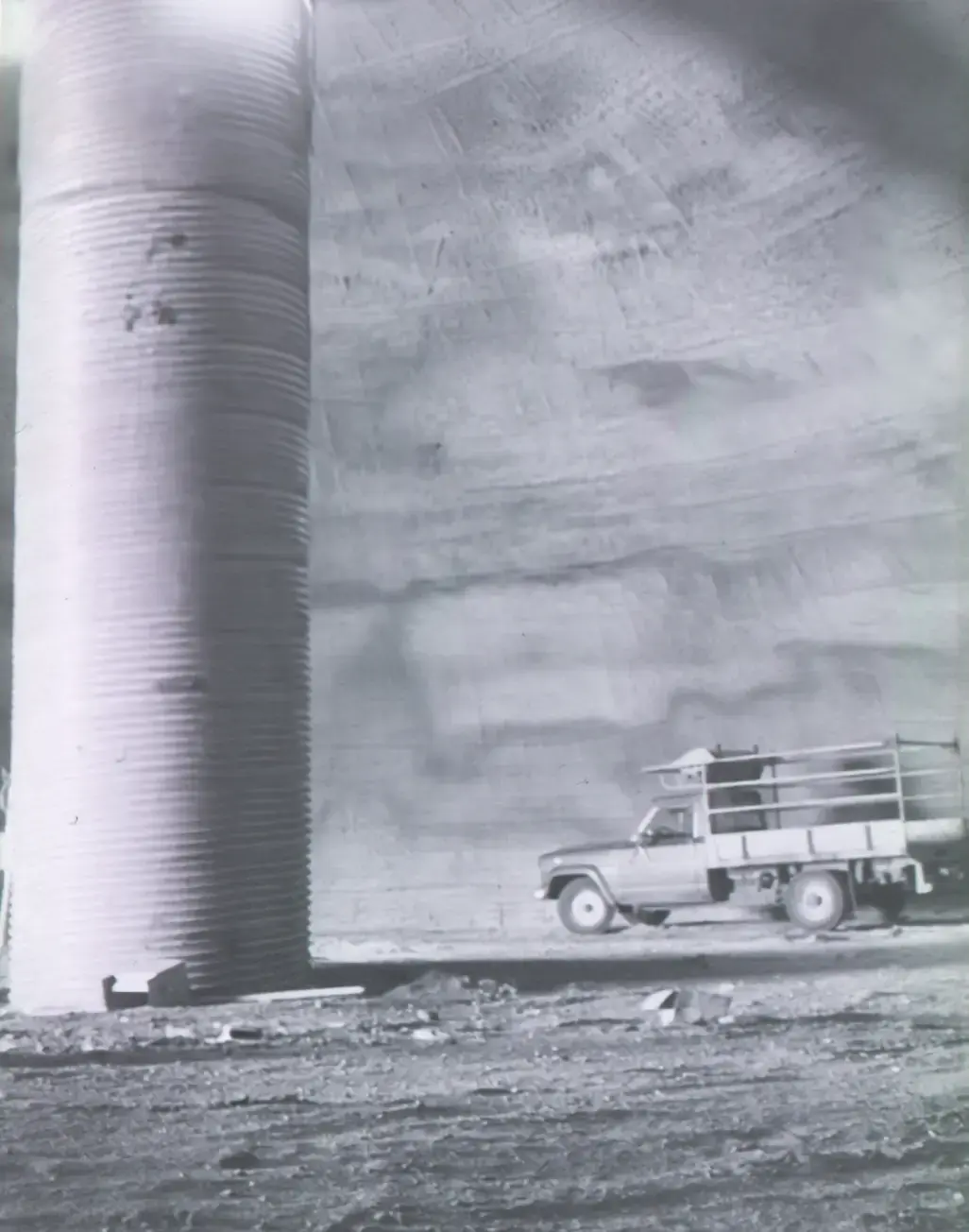

This photo of the Souths Incorporated truck inside the shell illustrates the scale of the massive undertaking that was this first Monolithic Dome. The Souths had no experience spraying shotcrete, but after getting frustrated with the shotcrete company they had hired, they purchased the company’s equipment and applied the shotcrete themselves.

The first dome was coated in an industrial primer before a layer of shotcrete was applied. Instead of using primer, which fails to prevent vapor penetration of the foam underneath, we leave the Airform in place after construction. With regular maintenance, the Airform will protect the dome structure indefinitely.

The first dome had the membrane peeled off after construction and a thin layer of shotcrete was applied. This proved to be a very bad idea. Now, the Airforms used in construction are left in place and act as a single-ply roofing membrane.